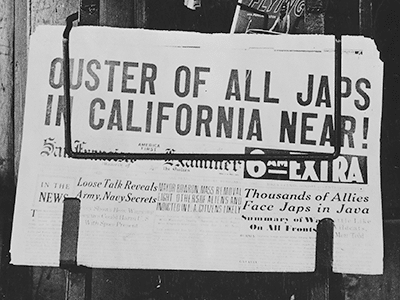

In 1942 at the height of World War II, Fred Korematsu, a 23-year-old Japanese-American living in California, disobeyed the order to report to an internment camp because he felt it violated his 5th Amendment right to due process and his civil liberties. He was arrested, convicted, and appealed his case. In 1944, Korematsu v. United States was heard by the Supreme Court, where Mr. Korematsu’s conviction was upheld. A federal judge in San Francisco overturned his conviction in 1983, but Mr. Korematsu’s Supreme Court decision still stands.

What lessons can we learn from our history? How does the Supreme Court decision impact our society today? The case became relevant again in 2018 during Trump v. Hawaii, where the Supreme Court upheld the Trump Administration’s policy of banning most residents of seven countries from entering the U.S. The Court upheld the ban on a 5 to 4 vote, rejecting arguments that the ban was “anti-Muslim.” However, Chief Justice wrote, “Korematsu was gravely wrong the day it was decided, has been overruled in the court of history, and—to be clear—has no place in law under the Constitution.” Dr. Karen Korematsu, daughter of Fred Korematsu, speaks with ACTEC Fellow Hung V. Nguyen about her father’s history, the Supreme Court decision, and its relevance to protecting civil liberties in modern society.

Resources

- Fred T. Korematsu Institute

- U.S. v Korematsu: An Account

- Civil Liberties Act of 1988

- Facts and Case Summary — Korematsu v. U.S.

- What we can learn from Fred Korematsu, 75 years after the Supreme Court ruled against him, NBC News, 2019

- Considering History: Fred Korematsu’s Battle for an Inclusive America, The Saturday Evening Post, 2022

- The Importance of Cultural Competence in Estate Planning

Transcript

Introduction

ACTEC Fellow Terrence M. Franklin: Civil liberties are rights guaranteed by the Constitution, such as freedom of religion, expression, and assembly. In 1942, Fred Korematsu, a 23-year-old Japanese-American living in California, disobeyed the order to leave behind his day-to-day life and report to a “relocation camp” with other citizens of Japanese ancestry following the attack on Pearl Harbor. He challenged the order because he felt it violated the 5th Amendment right to due process and therefore his civil liberties, a challenge that went all the way to the Supreme Court in Korematsu v. United States. Fred was arrested and convicted, and he lost at the Supreme Court.

How does that Supreme Court decision impact our society today? What lessons can we learn from our history? We are honored that Dr. Karen Korematsu, of the Korematsu Institute and Fred’s daughter, joins us today to share her father’s story and discuss the importance of protecting civil liberties. ACTEC Fellow Hung Nguyen will get us started.

Overview of Korematsu v. United States

Hung V. Nguyen: Good afternoon, Dr. Korematsu. Thank you for being with us today. So, you share a famous last name with a major U.S. Supreme Court decision which I would say is actually infamous. Can you tell us how you are related to the main party in that case?

Dr. Korematsu: My father was Fred Korematsu who had the infamous, or landmark Supreme Court case, Korematsu v. United States. And, my father was born in Oakland California, so he was an American citizen and lived until he was actually 86 years old and passed away in 2005.

Hung V. Nguyen: So, what happened in Korematsu v. United States?

Dr. Korematsu: With the bombing of Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, of course, the US was – went into the war against Japan. And President Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066 on February 19, 1942, which actually gave the military the ability to forcibly remove anyone of Japanese ancestry from the west coast. This was half of Washington to the west if you start with the demarcation line starting in Canada, down through Oregon to the west, all of California, and half of Arizona to the west.

And it didn’t matter if you were even born in this country or an American citizen. You basically only had maybe a few days to decide what you were going to take with you, because you had to leave everything behind, sell it on 10 cents on the dollar. You didn’t know where you were going, you didn’t even know the weather conditions, and you didn’t know when you were coming back. And, So, in that case, my father thought this was wrong. Also, because all due process of law was denied with this executive order.

No one had access to an attorney, no one was even charged with a crime, and no one had their day in court. So, my father thought this was wrong, that he was an American citizen. He learned about the Constitution in high school and thought he had rights as an American citizen. And, So, he decided not to report to a detention assembly center, prison center, like his family. He was living in San Francisco Bay area in Oakland California. San Leandro was where he was arrested, and 30 days later, on May 30, 1942, just a little over 80 years ago. And he was sent to a federal jail in San Francisco, and he had a visitor. Mr. Earnest Besig, who was then the executive director of the Northern California Affiliate of the American Civil Liberties Union, who was looking for a test case because he thought it was unconstitutional and visited my father in jail and asked my dad if he’d be willing to take his case, if need be, all the way to the Supreme Court. And my father thought, for sure by the time it reached the Supreme Court, that they would see it was unconstitutional. So, he always had that hope.

Supreme Court Decision in Korematsu v. United States

Hung V. Nguyen: So, when the case reached the US Supreme Court, did they side with your father?

Dr. Korematsu: No, unfortunately not on December 18, 1944, they still ruled against him. However, it was not unanimous. It was a 6 to 3 decision, and the three dissenting opinions are most important and relevant today.

Justice Robert Jackson referred to my father’s case as, “This lies around like a loaded weapon ready for anyone to pick up and use as a plausible cause,” I’m paraphrasing. And actually, after 911, 2001, Attorney General Ashcroft decided my father’s Supreme Court case is a possible reason to round up Arab and Muslim Americans and put them in American concentration camps.

Justice Owen Roberts, not related to Chief Justice, said it was “unconstitutional” and Justice Murphy referred to the incarceration as the “Ugly abyss of racism.”

Hung V. Nguyen: So, what happened to your family and families just like yours, of Japanese ancestry during this period of time, including after the case?

Dr. Korematsu: They were forcibly removed from their homes. They could only take with them what they could carry in two hands and first were sent to converted racetracks. San Francisco Bay area was Tanforan Racetrack that was converted into a prison camp.

All they did was whitewash the walls, put an iron cot in it, Army blankets, light bulb, dirt on the floor, but it still smelled like manure. And we treat animals better than we treated Japanese-Americans. Because the story of the Japanese-American incarceration really is the inhumanity that was against them. And they had to live that way for three or four months before they were sent off to one of the ten permanent, so to speak, Japanese-American concentration camps across this country until the end of the war.

The other detention assembly centers were up and down the west coast, either racetracks or converted horse stalls on fairgrounds or sports centers. So, this is over 120,000 people of Japanese ancestry were forcibly removed from their homes and to live in these kinds of conditions until the end of the war.

Now the government knew that the Japanese-Americans were not dangerous, so community leaders from outside helped people get jobs if they could go east. You couldn’t go west until the end of the war, but you could go east. My father went to Detroit, Michigan eventually and so that’s what happened to them. And then at the end of the war, the Japanese-Americans were only given $25 and a bus ticket and that was it to start over their lives.

Hung V. Nguyen: During this period of time, were families uprooted and were they separated when they went to these separate internment camps?

Dr. Korematsu: The day after Pearl Harbor, December 7, 1941, over 2,000 Japanese nationals were picked up by the FBI and sent off to Department of Justice camps. They were just stripped away from their families and the families didn’t even know where they were going. They were dangerous people like Buddhist priests and teachers who were teaching Japanese language, and community leaders. Those type of dangerous people. And to be noted, there was never any evidence of any spying or espionage on the West Coast. I mean that’s what was learned after my father’s case was reopened in 1983. And, so, this was the outright racism that was happening at the time.

And part of the back story was even agriculture. Because many of the farmers – and up and down the west coast – when the Japanese nationals Issei, first generation like my grandfather, were doing well in agriculture it was the same old story, “Well they’re taking away our jobs, send them back to Japan.” We’ve done that to the Chinese when they were doing well and working on our railroads, and we even done that for Hispanics coming up from Mexico and South America to work in our fields, to help us grow our agriculture in this country

Hung V. Nguyen: So, your father’s conviction was eventually overturned in 1983. I believe the trial court found that the U.S. government had been hiding evidence that would have been exculpatory in terms of the dangers posed by Japanese-Americans to the west coast. Can you talk about that case a little bit?

Dr. Korematsu: Yes, actually, it was Professor Peter Irons, who was a legal historian and lawyer, was doing research in D. C. as he was going to write a book about the World War II Supreme Court cases. And he found the evidence along with another researcher Aiko Herzig-Yoshinaga, that proved there was no reason for the Japanese-Americans to be incarcerated.

At the time of my father’s Supreme Court hearing in December 18, 1944, the government or the Department of Justice actually had lied to the Supreme Court, had altered evidence, and destroyed evidence. So, always beware. And on that basis they were able to reopen my father’s case along with two other Supreme Court cases, Hirabayashi and Yasui. Those had to do with the curfew. My father’s case was disobeying the military’s orders and that’s how his case was reopened on that evidence.

Supreme Court Decision in Trump v. Hawaii

Hung V. Nguyen: So, while his conviction may have been overturned, the decision in Korematsu, there’s been some debate about whether or not it’s still good law because of the U.S. Supreme Court decision in Trump v. Hawaii. Can you talk about that?

Dr. Korematsu: Yes, actually next year will be the 40th anniversary of my father’s Coram Nobis legal case or the Coram Nobis cases. Coram Nobis, in case some of you don’t know, because it is a little unknown procedure, but the evidence was lied to the courts. And, so, the conviction was …my father’s conviction was vacated in 1983, so he no longer had a federal prison record but the Supreme Court case still stood. So, the Supreme Court can only overrule itself.

So, when the Muslim ban was issued on January 27, 2017, after that time, the Attorney General of Hawaii decided to fight this against the president in Trump v. Hawaii. Because it was clearly religious profiling, it was banning the Muslims and Arabs from coming into this country. And, at first, they called it – I should not — the Muslim ban. Well, of course then there was a lot of pushback in this country. And then they called it the immigration ban. Well, that didn’t go over very well. Then they cited well, okay, we’ll include Venezuela, and we’ll just call it the travel ban. And, so, this is how these euphemisms and what happens to this country and how it gets discounted.

And, so, when Chief Justice Roberts, who wrote the Majority Opinion said – you know he, of course, upheld the Muslim ban, Muslim travel ban, but because I was asked to submit an Amicus brief and a friend of the court brief along with the other two children of Gordon Hirabayashi and Minoru Yasui. It was to remind the court of my father’s Supreme Court case and the other cases and the dangers of overreaching of power, that there is a reason that we have the different branches of government.

And, so, because Justice Sotomayor had given her…issued her really scathing, dissenting opinion that referred to my Amicus brief and reminded the courts of Korematsu v. United States. Chief Justice Roberts gave an opinion. He said, “Well Korematsu is overruled in the court of history,” but it did not have anything to do with the majority opinion in the Muslim travel ban. It was what we call in law, Dicta, it was his opinion. So, Therefore, Korematsu v. United States still stands. It certainly has been discredited but it can be used in another Supreme Court case as precedent. Depending, of course, on what it is.

Legacy of Korematsu Case

Hung V. Nguyen: So, what would you say is your father’s legacy? What lessons can we learn from the Korematsu matter and apply them today?

Dr. Korematsu: Well, now we have a special day that’s in honor of my father. It’s Fred Korematsu Day of Civil Liberties and the Constitution. It’s important to emphasize it’s about our civil liberties and the Constitution and the emphasis is on our civics. On our civics participation and that importance, and that’s the way my father led his life.

It’s on his birthday of January 30th. States California went first, Hawaii, Virginia, Florida, New York City, even Arizona governor signed the bill earlier this year that establishes the day in perpetuity. And an opportunity for education, a push for civic participation, but we hope other states will follow. It’s not a holiday yet, working on that, but it’s going take other States to come along.

But my father, what he said, and I’ll quote, “To stand up for what is right and don’t be afraid to speak up.” Certainly, that’s what the Attorney General of Hawaii felt when he decided to fight the case in court. And the lesson is also how one person can make a difference in the face of adversity.

My father was not supported by his own Japanese-American community when he was sent over to the Tanforan Racetrack, the assembly prison center. After his arrest, all through the time of his even going to the incarceration camp in Topaz, Utah, where he and his family were.

And this was 120,000 people of Japanese ancestry that were denied any type of due process. And he fought this in hopes that he would always be able to reopen up his case and even at the time in 1983 because of the Redress and Reparations movement his Japanese-American community said to him, “Well, Fred, if you reopen up your case you may lose and you’re going to hurt our chance for Redress and Reparations.”

And because my father didn’t listen to anyone – but he was never bitter or angry, he never blamed anyone. He felt that the government was wrong he was right to take a stand. And that’s what he crisscrosses this country, trying to educate people so that something like the Japanese-American incarceration wouldn’t happen again because he was so afraid that it would.

And we need to learn to respect each other. I never thought we’d get to this point in my lifetime where we’d have to talk about that, or even teach children that. We can agree to disagree, to find those principles that we do agree on and to work from there. And, because we all love this country, we all want best for our communities, we all want best for our families. And there is such a divide and the hate and violence that we’re seeing now against African-Americans and Asian-Americans has got to stop.

That we all need to be accountable. That it’s not somebody else’s problem. That everyone, what I say is also that I learned from my father, is to be part of the solution and not the problem. And if we all work together, if we all had that conversation of sharing our own stories, as my father did, and to appreciate each other’s differences and not to be afraid of them. Because prejudice is ignorance and our most powerful tool that we have is education.

That’s what we do at the Korematsu Institute, Fred T. Korematsu Institute, here in San Francisco. We’re a national organization. We work with teachers, educators, and my age range of audience are kindergarteners to judges.

This is why my father’s legacy resonates on so many different levels. Because it’s about social justice. It’s about upholding our diversity and inclusion and equity so we can try to eliminate this violence.

And, also, just to speak to what’s happening now in social media. To understand that 70% of the misinformation and disinformation is retweeted and sent across our social media. So, we all need to question what we hear and not take for granted somebody else’s opinion. That we need to learn what the facts are and be truthful ourselves.

Hung V. Nguyen: Thank you very much Dr. Korematsu for being here today, for educating us, for enlightening us, and for continuing your work for social justice. Thank you.

Dr. Korematsu: My pleasure. Stand up for what is right.

Conclusion

ACTEC Fellow Terrence M. Franklin: As Dr. Korematsu said passionately, “be part of the solution!” Educate yourself about social justice. Question the information you read on social media and be mindful of what you share. Do not be a passive observer when you notice racism and injustice. “Stand up for what’s right.”

Please visit ACTEC, actec.org/diversity for more information and resources on this topic and make sure you subscribe to ACTEC’s YouTube Channel to be informed of new videos as they become available.

Featured Video

Landmark Civil Rights Cases Decided by the Supreme Court

Author and Professor Christopher Schmidt reviews the history of critical Supreme Court civil rights and equality cases that everyone should know.

Planning for a Diverse and Equitable Future

ACTEC’s diversity, equity, and inclusivity video series analyzes issues surrounding racism, sexism, and discrimination in all its forms to combat inequality.